The Vampire Voss

The Vampire Voss Lavender Vows

Lavender Vows Sanctuary of Roses

Sanctuary of Roses A Lily on the Heath

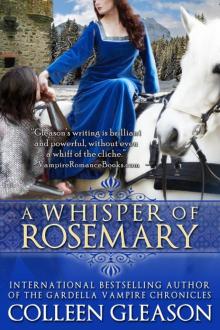

A Lily on the Heath A Whisper Of Rosemary

A Whisper Of Rosemary The Rest Falls Away

The Rest Falls Away The Clockwork Scarab

The Clockwork Scarab Roaring Midnight

Roaring Midnight The Vampire Dimitri

The Vampire Dimitri Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology

Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology The Vampire Narcise

The Vampire Narcise When Twilight Burns

When Twilight Burns The Bleeding Dusk

The Bleeding Dusk As Shadows Fade

As Shadows Fade Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5)

Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5) Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow)

Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow) Sinister Sanctuary

Sinister Sanctuary Night Beckons

Night Beckons The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4)

The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4) The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1)

The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1) Lavender Vows tmhg-1

Lavender Vows tmhg-1 Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1)

Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1) Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology

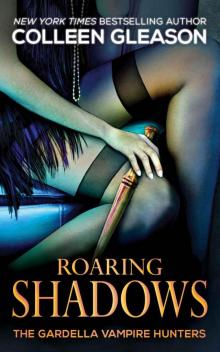

Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology Roaring Shadows

Roaring Shadows The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3)

The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3) The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1

The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1 The Chess Queen Enigma

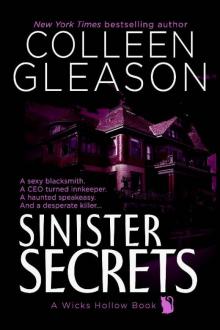

The Chess Queen Enigma Sinister Secrets

Sinister Secrets A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8)

Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8) The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2)

The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2) Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10)

Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10) Sinister Summer

Sinister Summer Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4)

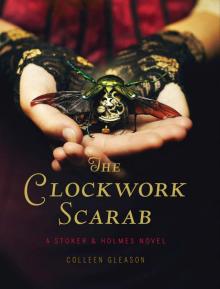

Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4) The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel

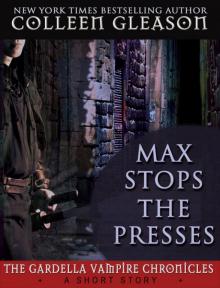

The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel Max Stops the Presses

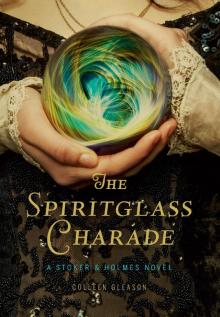

Max Stops the Presses The Spiritglass Charade

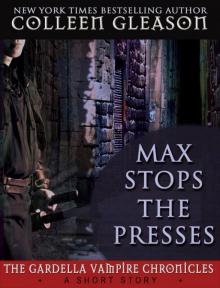

The Spiritglass Charade Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story

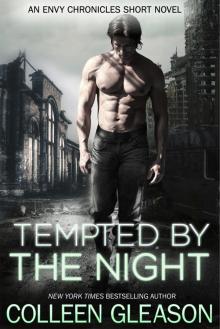

Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story Tempted by the Night

Tempted by the Night