- Home

- Colleen Gleason

The Zeppelin Deception Page 10

The Zeppelin Deception Read online

Page 10

Why that was such an interesting, scandalous fact was a mystery.

I was, however, swooningly relieved I’d never visited Newgate Prison. That would have been so much more difficult to explain.

“You’re going to have to apologize to Mr. Oligary immediately,” Florence said, once she’d exhausted all of her lamentations. Her expression was tight with fear. “Perhaps he’ll see the humor in it—although I’m not sure how— Whatever were you doing there, Evaline? How could you do such a thing?”

I gaped at her. “It’s not like I was visiting an opium den!” (Thank Pete she’d never learned about that incident.)

“Why is it such a scandal that I went into Scotland Yard?” I snapped.

For a moment, I thought she was going to strike me. I reared back a little, suddenly wary, but she didn’t raise her hand to me.

“I don’t know what’s gotten into you, Evaline, but I don’t like this recent manner you’ve adopted. It’s that Mina Holmes, isn’t it? You’ve been consorting with her—”

“I haven’t seen Mina since my engagement was published,” I said from between gritted teeth. “An announcement that was published without my knowledge or permission, might I remind you. So don’t blame Mina.”

I wanted to say, Blame yourself, but I managed to hold my tongue.

“Young women simply don’t go to the Metropolitan Police,” Florence said in a slightly calmer voice. But her teeth were clamped together. “It’s not proper.”

I shook my head. I didn’t understand why, but I knew she wasn’t going to explain it. I wasn’t even certain she knew why it wasn’t proper.

“Well,” she cried suddenly, “what are you waiting for? Get up and make yourself presentable. You’ll have to send a message to Mr. Oligary straightaway.”

I don’t know why, but I let her bully me into getting out of bed and ringing for Pepper. I sat sullenly while, in a repeat of yesterday but over a much longer span of time, the two of them fussed over me.

During a short interlude when Pepper went to get my best silk petticoat from the laundry, Florence shoved a paper and mechanical ink-pen in front of me and insisted I write a note asking Ned to call soonest.

“We need a telephone,” she muttered. “For times like this. As soon as you’re married, we’ll have one installed.”

I wrote the blasted note.

But when Florence swept from the room to have Brentwood find a messenger to deliver it, I looked down at the extra note card she’d brought in case of mistakes.

And before I quite knew what I was doing, I was writing another message.

To Lady Cosgrove-Pitt.

Miss Holmes

~ Wherein We Question the Wisdom of the Bard ~

I couldn’t believe Grayling hadn’t stopped me. It was both a shock and relief that he hadn’t recognized me, even with my disguise.

And also—how unfortunate that he’d managed to insert himself into my investigation at a most inopportune moment! I hadn’t even been able to get into Mr. Boggs’s house to examine the crime scene, and I didn’t know when I’d have the chance to return if he was going to be lurking about. And what had Grayling been doing there anyhow?

I maintained a masculine stride as I walked down the block, turning in the direction of my own house. I was curious as to whether more constables were waiting for my return, and hoped that they weren’t so I’d be able to slip inside and retrieve some important items—in particular, more funds and clothing.

I frowned as I went on, carefully avoiding icy patches and using my walking stick to assist me when I had no choice but to step on something slippery. I’d never realized how useful such an appliance could be.

We females have nothing similar in our accessories—although perhaps a parasol would be an appropriate substitute. I thought there might be a female Egyptologist who employed one on a regular basis; I would have to investigate that matter further. Perhaps she’d even outfitted it as a weapon. I could imagine many ways in which a good, solid parasol handle would be quite useful.

How could Grayling not have known me? We’d very nearly bumped into each other, and my glasses and hat had gone askew.

However, I had donned an impervious disguise. It was impossible for anyone to see the real Mina Holmes beneath it.

I supposed Shakespeare was incorrect in his assessment that love looks not with the eyes but with the mind—but I exaggerate, of course, as not for a moment did I suppose Grayling harbored that particular sentiment toward me.

Certainly he didn’t.

It was ludicrous to think so, and the fact that he hadn’t recognized me only further validated that fact.

My frown grew deeper as I turned onto the street where I lived. I had no idea why that ridiculous Shakespearean passage had lodged in my head—except for the fact that it merely substantiated any affection—or, rather, lack thereof—the inspector might have entertained toward me.

I gave myself a severe mental talking-to about allowing my thoughts to keep running around the same cogwheel and turned my attention to my environment. I couldn’t take the chance of being caught off guard, despite being so well disguised.

As usual, chimneys burped steam and black smoke into the air, and in the distance, I could see the shape of sky-anchors wafting above pitched rooftops in the more crowded parts of London.

The street on which I was traversing was empty of waiting carriages, and there was a messenger boy approaching a residence two houses down from mine and across the street. Other than that, I saw no sign of life but for a few pigeons casting about for meager sustenance during this winter month and a cat eyeing me from the window of our neighbor’s house.

Nonetheless, I walked past my home and down the street. I couldn’t see much of the small courtyard behind the house, but the gate through which I’d blithely walked during my escape was closed, and there weren’t any recent footprints in the crusty snow. That meant no one had been there since yesterday, for there’d been a bit of snow last night. That was a good sign.

I was just turning around so I could slip into the rear courtyard when I heard a loud mechanical roar approaching very quickly. It startled me—not only because it was so loud and it cut through a relatively peaceful moment, but also because I was certain I recognized it.

Drat!

Before I could decide what to do, a ferocious-looking steam-cycle zoomed up the street and paused next to me with a smooth rumble. My instinct was to ignore it, but no one would believe that a random passerby wouldn’t look at such a monstrosity, and so I deigned to turn my head—all the while still in the character of my various-accented gentleman.

“Get on,” Grayling shouted over the roar. I couldn’t hear him over the noise, but I could see his mouth form the very specific words. Nor could I see his eyes behind the goggles he wore, but I suspected they were the cool gray hue they usually were when he was annoyed with me. (Although why he should be annoyed with me in this case was an excellent question.)

I debated internally for only an instant, then acquiesced. Better not to draw attention, and the sleek bronze steam-cycle—which I was certain didn’t actually run on steam, but something more illicit—was certainly conspicuous as it sat there, gleaming in the street. It sent up curls of white and black smoke from the collection of bronze tailpipes that jutted from beneath its rear.

As I prepared to climb onto the vehicle—a transport I both admired and despised—I realized I was wearing trousers. That made everything so much simpler.

And, at the same time, all the more awkward.

After all, I had to throw my nether limb (even now as I write this, I fairly blush to think about it) over the seat of the cycle, and then to settle my posterior on the cushioned seat behind the inspector. On the previous occasions during which I’d climbed aboard the loud, fast monstrosity, I had been garbed in layers of petticoats and, once, split skirts—which had cloaked my lower limbs and obscured the shape thereof as well as dulled the vibration of the machine itself

.

But now, as I settled behind him, riding astride in a very unladylike—but truly convenient—manner, I felt far more stable than I had during the other journeys on the cycle. No sooner had I placed my feet on the handy steps on either side of the machine and wrapped my arms around his waist than the cycle gave a little jerk and we were off. My fingers were a bit clumsy inside the special gloves that obscured their shape, but I managed to hold on to his heavy coat.

However, my hat was gone in an instant and his muffler flapped in my face. I took to burying my eyes in Grayling’s broad, warm back in order to protect it from the bitingly cold wind. Along with that of chill and damp wool, I inhaled the pleasant and familiar scents of lemon and peppermint that usually clung to the inspector, and closed my eyes.

But they popped open when we roared around a corner and jounced wildly over a curb. As we screeched onto another street with a sharp turn, I lost the walking stick I’d lodged under my arm. I was grateful I’d tucked my small satchel under the long greatcoat I wore, so it was protected from the extreme speed and jolting turns we were bound to continue to make. Grayling was not what one would call a circumspect driver.

I had no idea where he was taking me, and after a brief moment of hope that it wasn’t to the Met, I had another, more diverting thought.

Apparently Grayling had recognized me after all.

At last, the steam-cycle came to a halt on a block not far from Glaston Mews. It was a residential area, with two street levels above us accessed by slender mechanized lifts. The lifts appeared functional and relatively safe, as long as one didn’t crowd too many people inside. But for simple protective grids, the sides were open—unlike the street-lifts in the more expensive areas of the city, which were completely enclosed and boasted elegant copper and brass decor.

Narrow row houses crushed up against each other, crowding each block in every direction. The houses were made from dull, creamy brick that were dusted gray from decades of smoke, but each entrance was neat and devoid of debris or refuse. Curling bronze and copper railings enclosed their small porches, and small curved metal roofs over each door offered some protection from the elements. Someone had even shoveled the snow from the walkways and up most of the steps.

A Street-Agitator trundled down one side of the narrow street, sweeping up trash that hadn’t fallen into the small canals on either side of the throughway. The walkways on the higher levels were narrow but appeared solid, and I could see that there were more single-story flats accessed by each bridgelike passage above. Cross-bridges attached the opposite sides of the air canals at approximately every other block, and were situated conveniently next to the street-lifts.

Grayling did something, and the steam-cycle purred into silence. I climbed off with great difficulty—for my nether limbs were unsteady and a little numb from the great vibrations of the vehicle—and I certainly wasn’t accustomed to (nor overjoyed about) the vulgarity of lifting a leg high up over the seat of a vehicle. Thus, I nearly lost my balance while dismounting, and it was only the inspector’s quick reaction that kept me from stumbling on my shaking knees.

He steadied me and I stepped away, suddenly feeling shy and unsettled. Grayling didn’t seem to notice, for he’d turned his attention back to the monstrous cycle. With the push of a button, the conveyance seemed to collapse in and onto itself—taking on the appearance of nothing more than a useless jumble of metal. That apparently wasn’t enough, for next the inspector tossed a canvas over the mess of pipes and brass pieces. Somehow the canvas adhered to the pile—strong magnetization, I concluded, possibly electrical (which would be illegal, of course)—and when he turned from it, the formerly gleaming, sleek cycle now resembled a nondescript lump of stone. He’d parked just inside a narrow alley, which also contributed to the camouflage.

“This way, then,” Grayling said, and gestured to the street-lift.

I hesitated, but stepped inside. He turned to push a lever on the inside wall—I noted with surprise that there didn’t seem to be a fee to ascend—and that was when I saw my mustache clinging to the back of his coat.

I choked on a gasp that was both horror and giggle and snatched it back. He saw me and shook his head. I thought a smile might have tickled the corners of his mouth, but if so, it was quickly suppressed.

The street-lift stopped at the top level, where the houses were slightly less blackened from smoke and where there was a bit more sunshine—relatively speaking. No sooner had we taken a step off the lift, I heard ecstatic barking and wild howling from several doors away.

Angus.

I’d recognize his voice anywhere.

Until then, I’d suspected but hadn’t known for certain that Grayling had taken me to his home.

One must understand that, despite the fact that I am most certainly what they call a feministe, and that I generally do my best to adhere to society’s logical etiquette and prohibitions, it was quite an unsettling idea to think that I’d be visiting the home of a single young man by myself.

Still, I certainly couldn’t direct Grayling to take me to Pix’s hideaway, and I was in dire straits—being wanted for murder and having nowhere else to go—and so I had no option other than to follow him up the three steps that led to what was presumably his door.

Angus was beside himself when Grayling opened said door. He (the canine) spilled out onto the narrow walkway, tumbling over his ears with his mechanical leg clattering all the while as he jumped, rolled, squirmed, and otherwise made himself appear ridiculous in his excitement. He bounced and bounded so violently that he slammed into the railing of the raised walkway that looked down over two levels to the ground. The force of impact didn’t dull Angus’s enthusiasm in the least.

“Erm…uh…” Grayling seemed hesitant to invite me inside, so of course I took matters into my own hands and stepped across the threshold.

The place was small but neat—although there was evidence that Angus had been bored, for a shredded cushion decorated the floor in a corner of the two-room apartment. The flat was sparsely furnished, as one might expect for a bachelor employed by the stingy Met. There were two armchairs around a small table in the main room, tucked near a fat, mechanized wood stove of a very recent design that served a dual purpose: for heat as well as food preparation, without all of the ash and mess of most stoves. There was even a warming drawer, which I thought would be most convenient—one could place one’s tea water and a small egg cake inside before bed, and in the morning, it would be perfectly heated.

A small pantry and cupboard with a tiny eating table seemed the extent of his kitchen area. I noted a door that was partially open through which I discerned the foot of a neatly made bed (I immediately averted my eyes), and a second door that likely led to what one would call a gentleman’s lounge. I most certainly didn’t find it necessary to look too closely in that direction either.

Two windows allowed some light, and the other two walls were covered with bookshelves. In the corner was a large table cluttered with mechanical parts and pieces, as well as tools I recognized as useful in the investigation of crimes: ocular magnifyers, fancy thermometers, expanding measurement devices that seemed to calculate all on their own, and other gadgets I couldn’t put a purpose to.

I realized Grayling hadn’t followed me inside; a glance onto the walkway told me he’d waited out there for Angus to do his personal business under a nearby tree that grew in a gigantic suspended pot on this street level. Since I didn’t find it necessary to supervise, I closed the door.

Now safely within the confined place, I smelled lemon and peppermint, as well as the faint scents of beef stew and wood smoke. The cushions on the chairs were comfortably worn, but the quality of their brocade was obvious. The rug on the floor was only a few weeks old. I deduced that Angus had contributed to the necessity of that recent purchase.

Since there was no longer any need to keep up the pretense, I was only too happy to remove the most uncomfortable elements of my disguise: the clumsy gloves,

the facial hair, the pads inside my cheeks (which had the disadvantage of making my mouth very dry, as the cotton absorbed every bit of moisture), the tiny wooden pegs that I’d inserted horizontally into my nostrils to change their shape, and the wig.

I was far more comfortable when Grayling and Angus (not in that order) erupted through the door. The latter immediately launched himself at me to sniff and paw at my trousered legs and masculine footwear. He seemed to be questioning my choice of attire, looking up at me with a short yip every so often during his examination.

“Yes, yes, it is I.” I found to my delight that I was actually able to bend over to pat the little beast on his bony head. He swiped at me with his long, agile tongue, unerringly finding the single sliver of bare skin between glove and coat. I subdued a shudder, but didn’t yank my arm away. The little beast could have no idea how disgusting such an action was, and I recognized he was merely showing affection.

When I returned fully upright, I saw that Grayling was watching me with an inscrutable expression. He’d removed his hat and hung it, as well as his coat, on a rack that—to my surprise—seemed non-mechanized.

“I suppose you want an explanation,” I said briskly in an attempt to forestall any sort of lecture or interrogation. “And before you say anything about me and a proliferation of dead bodies, may I point out that there wasn’t actually a dead body in today’s situation.”

He shook his head, and I swore his lips twitched again. “I suggest you not mention that to Mr. Boggs, Miss Holmes,” he said sternly. “For, to the contrary, there is, in fact, a dead body in this situation.”

“Surely you don’t think I had anything to do with it!” I realized my voice had pitched high and tight, and I struggled to bring it back to a normal level. “Ambrose!”

His name slipped out before I could stop it, and I don’t know who was more shocked—Grayling or myself. Angus, of course, was oblivious to my consternation, for he’d discovered a loose piece of trim on my shoe.

The Vampire Voss

The Vampire Voss Lavender Vows

Lavender Vows Sanctuary of Roses

Sanctuary of Roses A Lily on the Heath

A Lily on the Heath A Whisper Of Rosemary

A Whisper Of Rosemary The Rest Falls Away

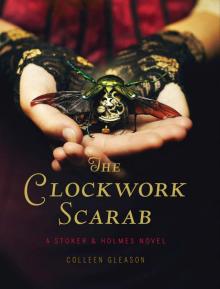

The Rest Falls Away The Clockwork Scarab

The Clockwork Scarab Roaring Midnight

Roaring Midnight The Vampire Dimitri

The Vampire Dimitri Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology

Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology The Vampire Narcise

The Vampire Narcise When Twilight Burns

When Twilight Burns The Bleeding Dusk

The Bleeding Dusk As Shadows Fade

As Shadows Fade Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5)

Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5) Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow)

Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow) Sinister Sanctuary

Sinister Sanctuary Night Beckons

Night Beckons The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4)

The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4) The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1)

The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1) Lavender Vows tmhg-1

Lavender Vows tmhg-1 Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1)

Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1) Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

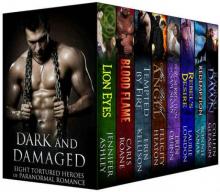

Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology

Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology Roaring Shadows

Roaring Shadows The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3)

The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3) The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1

The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1 The Chess Queen Enigma

The Chess Queen Enigma Sinister Secrets

Sinister Secrets A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8)

Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8) The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2)

The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2) Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10)

Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10) Sinister Summer

Sinister Summer Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4)

Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4) The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel

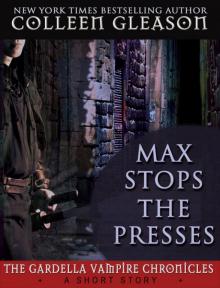

The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel Max Stops the Presses

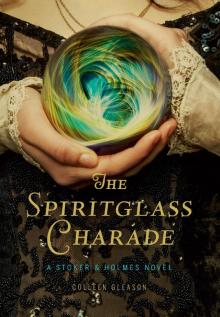

Max Stops the Presses The Spiritglass Charade

The Spiritglass Charade Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story

Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story Tempted by the Night

Tempted by the Night