- Home

- Colleen Gleason

The Chess Queen Enigma Page 5

The Chess Queen Enigma Read online

Page 5

“That hardly helps us at all! Wasn’t there anything else? You’re a Holmes, aren’t you? If it were your uncle, he’d be able to tell me everything about who wrote it just by looking at it!” Miss Stoker’s frustration was not the least bit becoming to a genteel young lady. I hoped she didn’t demonstrate this sort of behavior while with Princess Lurelia.

The internal reminder of the Betrovian princess had me checking the small clock on my bureau. “Drat! It’s nearly eight. You’ve put me off my toilette, Evaline, and now I am going to be late. The princess’s carriage should be here any time.”

“Right, then. I suppose I shall just have to continue this investigation on my own.” Apparently Miss Stoker wasn’t quite ready to give up her overt frustrations; but I had no energy or attention to spare her sensibilities.

She flounced out of the room. A moment later, I heard her carriage drive off, and I wondered if she would actually direct Middy to take her to the ball or whether she would indeed take investigative matters into her own hands. That could be quite entertaining, watching Miss Stoker attempt to observe and deduce and follow a trail of clues.

However, I would be greatly irked if she was absent from the ball and I was relegated to playing nursemaid to the drab, uninteresting Lurelia. We’d had very little interaction with the princess due to the events last evening, but Miss Adler had made it clear Evaline and I were to begin our chaperonage of the young woman tonight.

I was just pulling on fingerless gloves of midnight blue lace, which reached halfway up my forearms and matched my sparkling, diaphanous over-gown, when Mrs. Raskill appeared in the doorway. She wore an expression somewhere between astonishment and irritation (she hated being interrupted during her work). “There is a person here who claims he is to deliver you to a ball?” Her tone ended on a definite upswing, as if posing an inconceivable question to either me or herself.

I snatched up my wrap (also of delicate dark blue lace, but decorated with swashes of tiny copper- and topaz-colored gems) along with a small handbag and hurried from the room.

When I caught sight of the tall, broad-shouldered figure standing in the small vestibule, I jolted to a halt. “Inspector Grayling?”

At first I thought he must have come to discuss the case of the missing letter, but then I realized he was dressed formally in black coattails and a crisp white shirt. As if to attend a ball. He even held a top hat in one hand. And he was wearing spotless white gloves.

All thoughts seemed to leak from my brain and I could do nothing but stand there gaping. He looked rather . . . imposing, and . . . well, gentlemanly. One might even use the term “handsome.”

“Miss Holmes.” He folded his tall self into a brief, stilted bow.

“Inspector Grayling, what on earth are you doing here?” I was acutely aware of Mrs. Raskill hovering in the doorway between the kitchen and the parlor, close enough that she could see and hear the exchange happening in the foyer.

His freckled, pleasantly ruddy cheeks darkened slightly. He’d done an excellent job shaving this evening, except for a tiny nick near the left corner of his square jaw. “I am to be your escort to the Welcome Ball this evening. I thought . . . I was under the impression you had been informed.”

“Right, then. Of course,” I managed to say. My cheeks were warm. “Shall we proceed?”

“Indeed.” He seemed as much at a loss for words as I.

But he did remember to offer me his arm, which I took after preceding him through the door. Grayling led me down the short walkway to a waiting carriage, which bore the crest of Her Royal Highness.

I walked gingerly, taking great care not to catch my slender heels on any layers of skirt, petticoat, or lace flounces. It seemed as if every time I encountered Inspector Grayling, I was either tripping, falling, or dripping wet from an unexpected swim. I was determined not to repeat any such mortifying activities tonight.

Especially if he was to be my escort.

Heavens. Did that mean we must stay in each other’s presence all evening?

“What, no steamcycle tonight?” I attempted a jest as we approached our transportation.

Before Grayling could respond, the driver flung open the door. Please don’t let me trip.

I clambered as gracefully as possible into the depths of the carriage, firmly gathering up my skirts to keep wayward hems away from spiky heels and clumsy toes.

Thanks in part to my corset’s unyielding embrace, I was out of breath by the time I arranged my petticoats, skirt, bustle, wrap, and posterior on the plush velvet bench inside the carriage. Inspector Grayling, being a male and thus unencumbered by the travails of fashion, slipped in and settled himself with enviable ease.

The door closed and we were alone. The inside of the vehicle seemed to shrink. I could smell the faint scent of something lemony, tinged with peppermint and bergamot, wafting from the man across from me.

“It would have mussed up your hair and skirts,” he said as the carriage rolled smoothly into action. Apparently, having a royal driver eliminated the sharp lurching and jolting of a less lofty vocation.

“I beg your pardon?”

Grayling shifted, and I noticed one of his arms rested along the back of the bench on which he sat, while the fingertips of the other hand curled around the brim of his hat. He appeared much more at ease than I felt. Light filtered through the carriage window and made his dark coppery curls gleam like the sunset, or a roaring fire. “The steamcycle. I feared it would be an impractical mode of transport dressed as you are. It would be a shame—er—right. Miss Holmes, that’s a very nice dress. You look very—er—that is to say, one would hate to be the cause of it obtaining a streak of grease, or to become torn. Or—or wrinkled.”

I was thankful for the uneven light of the carriage, knowing it would help disguise the sudden flush heating my cheeks. “Indeed. And—er—thank you.”

I wanted to ask how he’d come to be assigned as my escort, but I couldn’t find the proper words. I could only assume Miss Adler and the princess had had something to do with it, and possibly even Lord or Lady Cosgrove-Pitt. Perhaps it was simply a matter of convenience, if we were both to be attending the ball. Fewer carriages to be ordered, and so on.

“Aside from the state of your attire, I was under the distinct impression you never wished to clamber onto that vehicle again.” His voice was wry.

“It is a rather . . . tenuous mode of transport.” I tried, and failed, to banish the memory of having to cling to his waist, pressing my face against his broad, solid back as we careened through the streets and alleyways of London. The momentary exhilaration of speed and the blast of fresh air had been overtaken by my constant fear of crashing. Two wheels are hardly stable enough to instill confidence when one is zooming along at high speed. “Nevertheless, one must never rule out any future possibilities.”

“I’m gratified you feel that way, Miss Holmes.”

We lapsed into silence for a short while, and then both began to speak at the same time. My voice trailed off into an awkward laugh.

“Pardon me, Miss Holmes,” he said, indicating I should continue.

“I confess, Inspector Grayling, I did not expect to find you in attendance at the Welcome Ball. Are you to be present in an official capacity, or as a guest of Lord Cosgrove-Pitt?” And his wife, the most dangerous and cunning villainess of our time? I could hardly imagine anything more awkward than encountering Inspector Grayling’s murderous relative whilst on his arm.

“A bit of both. After all, a crime was committed yesterday at the British Museum, during which I was present—as well as yourself—and there is significant pressure on everyone involved that this visit by the Betrovians goes well. Lord Cosgrove-Pitt—and of course your father—neither of them want another national embarrassment.”

I hadn’t realized he’d noticed my presence at the museum. “I see. But since when does a homicide investigator such as yourself become involved in a bit of petty thievery?”

“When that bit of petty thiever

y—and you know as well as I do, Miss Holmes, that the robbery of the Queen Elizabeth letter is more than mere petty thievery—is also connected to a murder, then a homicide investigator is most certain to be involved.”

“Murder?”

“Obviously you weren’t aware of the circumstances under which one of the museum guards was discovered. My apologies. I assumed that if there was a dead body to be lying about, as usual you would be found in its vicinity.”

The only reason I didn’t respond with a sharp retort was because of course he’d known I was unaware of the murder . . . and because I thought I detected a bit of humor in his voice. Clearly, he had offered me the information for some reason known only to him. Likely in order to obtain my assistance in the investigation.

“I encountered no dead bodies during my examination of the area where the robbery took place. But with it being in the dark and in the midst of such a crush of people—all of whom have no common sense about trampling over possible clues or scant traces of residue—there was little to be gleaned, even with my thorough examination. The culprit must have come from either the crowd itself—”

“Or the balconies above, Miss Holmes,” he interjected.

“I was just about to say that, hence my use of the word ‘either,’ ” I returned. “The attendees were searched before being allowed to leave, but of course the letter wasn’t found on anyone’s person. Which means either,” I said, giving him a quelling look, “the letter was hidden somewhere in the museum to be retrieved later, or—”

“Or the culprit left the way he—or she; let us be open-minded here, Miss Holmes—came. That is, from above.”

“Such an obvious point hardly needs to be mentioned.” I sniffed.

“Then I certainly need not point out the proximity of the location of the letter to the edge of the stage. And the fact that the lights surely were purposely extinguished—”

“—which means at least two individuals must have been involved.”

“Of course. But there was also the fallen statue,” he added smoothly.

My eyes narrowed at this unexpected comment. “Indeed. And what did you glean from the position and placement of that so-called fallen artifact, Inspector Grayling?”

“It wasn’t so much the position and placement—both of which were obviously deliberate. It was the symbolism in the particular artifact itself.” He held my gaze with purpose.

I saw no reason to respond and, in fact, had no opportunity to do so. The royal carriage pulled up to the entrance of the Midnight Palace, having obviously been given precedence over other, less important vehicles that still waited in queue to approach.

As the footman handed me out of the carriage, I realized Grayling had neatly redirected my attention from the details of the murder, while at the same time extracting from me all of the information I’d observed from the scene of the robbery. Drat him!

But since I was doomed to be in his company much of the evening, I was certain there would be opportunity to interrogate him about the murder.

Moments later, Grayling and I stood in a small trolley-like conveyance that was to transport us inside the social hall built by Mr. Oligary. I looked around with interest, noting a number of familiar faces—including Society’s most eligible bachelor, Mr. Richard Dancy, along with Mr. Southerby and Baron Leiflett. In the car ahead of Grayling and me was a man about the same age as my companion, and he seemed vaguely familiar. I couldn’t place him, even though I stared at the back of his blond head and watched him for a few moments. He was accompanied by three young women and another man, none of whom struck any familiar chord.

But as we approached the entrance to the Midnight Palace my attention was diverted. The structure had been completed three years ago, and was adjacent to Mr. Oligary’s more recent and modern project, New Vauxhall Gardens. While the Gardens were an outdoor pleasure park, the Midnight Palace was clearly meant to be a competitor to the Crystal Palace, which had been built for the Great Exhibition in 1851. Both locations were used for events, parties, and exhibitions, but the Midnight Palace was much smaller and more intimate—though no less grand and elegant.

Indeed, I had been inside the Crystal Palace and been stunned by the beauty of its glass roof and walls, but the Midnight was even more awe-inspiring. In fact, I was relieved to be transported along rather than attempting to ambulate under my own steam while taking in our surroundings.

The Midnight Palace glittered, from its outside walls—which were decorated with strategically placed sheets of glass, steel, and mirrors all designed to catch whatever meager sunlight might force its way through fog-shrouded London—to the inside. Our trolley car brought us smoothly and speedily through a grand entrance fettered with sparkling strips of fabric that acted as a waterfall-like curtain, and once inside my first impression was one of being delivered precisely where the structure’s name promised: into a starlit world.

The interior was swathed in darkness. Lush midnight blue, deep gray, and black furnishings, floors, and walls draped the hall like a night sky. Yet, the palace wasn’t dark, for sparkling lights glittered everywhere: on dusky canopies and curtains slung artfully overhead, on tapestries hanging from the walls at every height, and in the air on the same mechanical fireflies that darted and swooped through New Vauxhall Gardens.

Though the ceiling in the center of the large chamber loomed four stories over our heads, from all sides and in all corners were platforms—elevators, side-to-side trolleys, and even moving stairways—that raised, lowered, and transported guests on light-festooned conveyances. This had the effect of constantly moving, always twinkling bits of illumination.

“I’ve never seen anything so beautiful,” I said, trying in vain to cease from gaping.

“It is the perfect setting for you.”

I looked up at my escort, caught by the tone of his voice. It was hardly more than a murmur, as if he were speaking more to himself than to me.

He drew himself up stiffly when he saw my expression. “What I mean to say, Miss Holmes, is that your dress, and you—er—your—er—fripperies . . . that is to say, accoutrements are—”

“Ambrose, darling! Why, you look utterly splendid in those tails. The cut of that coat is exquisite; I’ve never seen you look so handsome. It quite shows off the breadth of your shoulders! We must get you spruced up more often, no? And Miss Holmes . . . what a glorious gown. Why, with all those jewels and sequins, you look like a night sprite who might have been spawned from this very glittery world. It suits you immensely.”

I turned to meet the calm gray eyes of Lady Cosgrove-Pitt.

Miss Stoker

Wherein Our Heroine Plods About the Dance Floor

I hadn’t had the chance to tell Mina there might have been an UnDead at the Welcome Event last night. She practically chased me out of her house. And after I’d done her hair so beautifully!

But that was fine with me. I hadn’t seen any evidence of UnDead at the museum. That didn’t mean there hadn’t been any, though. I just wasn’t perfect at being able to tell when there was a draft or when there was a vampire present. But it was clear I could no longer avoid patrolling the streets—because if the UnDead were back, I had to know.

And that was a fine excuse for leaving the Welcome Ball early.

Which I could do if Mina Holmes ever arrived and took my place entertaining Princess Lurelia. I cast a quick glance toward the long raised table, where Princess Alexandra and her husband, Prince Edward, sat conversing with the Betrovian Lord Regent, Lord Cosgrove-Pitt, Mr. Oligary, and several other dignitaries.

Princess Lurelia and I had been sitting with them and making stilted conversation about the weather until Princess Alix suggested we prepare for the dancing to begin. I practically bolted away from the table. Fortunately, the princess followed me, saving me from looking foolish.

“And here is your dance album,” I said to her, gesturing to the wall.

An array of thick copper slates hung in three rows. Each on

e was about the size of a small book. Because she was a guest of honor, hers had been assigned before she even arrived, and it was displayed prominently. I showed her mine, which was just where I wanted it—tucked in a low, corner slot where no one would notice. I had already scribbled my name on it, and now pulled down the album from its moorings. I thought I might “forget” to return it until the dancing was over.

“You see,” I told my companion, “I’ve had to write my own name—with this special pencil on the copper sheet. And—inside is a list of all the dances to be played tonight. If a gentleman wishes to dance with you, he will write his name on the line next to the one he chooses. There are waltzes and quadrilles and . . . what is this? A kelva? I’ve not heard of that.”

“The kelva is the national Betrovian dance,” Lurelia said. Her English was nearly perfect, with only a slight accent on occasion—which put to bed my theory that she was shy speaking an unfamiliar language. She examined her dance album, turning it over in delicate, white hands, for the first time showing interest in something. “They are rather like the chalkboards we use in the classroom. But heavier. And beautiful. The scrollwork and gears along the top are very pretty . . . oh, and the mechanisms work! Is that how the pages turn? And the pencil . . . is it engraving into the copper?”

“Yes, it’s a steam-pencil. It must be returned to its slot, to keep the water inside hot and create steam when you press on it to write. And after each set of dances, the slate is erased so it can be used again.”

“Oh. So we cannot keep them for a remembrance.”

“I’m certain Mr. Oligary would present you with yours if you asked, Your Highness. You are the guest of honor.”

“Please call me Lurelia. And I will call you Evaline, yes? I am sure we will become good friends while I am here.”

“That would be very nice.” At least she showed some sign of spirit and interest, but I still found her conversation mundane and her personality timid and colorless. Of course, I might be the same way if I was engaged to be married. I wondered what her fiancé was like; I hadn’t had the opportunity to ask.

The Vampire Voss

The Vampire Voss Lavender Vows

Lavender Vows Sanctuary of Roses

Sanctuary of Roses A Lily on the Heath

A Lily on the Heath A Whisper Of Rosemary

A Whisper Of Rosemary The Rest Falls Away

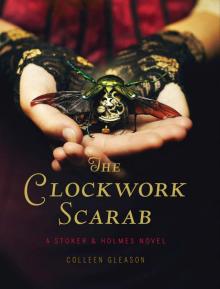

The Rest Falls Away The Clockwork Scarab

The Clockwork Scarab Roaring Midnight

Roaring Midnight The Vampire Dimitri

The Vampire Dimitri Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology

Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology The Vampire Narcise

The Vampire Narcise When Twilight Burns

When Twilight Burns The Bleeding Dusk

The Bleeding Dusk As Shadows Fade

As Shadows Fade Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5)

Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5) Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow)

Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow) Sinister Sanctuary

Sinister Sanctuary Night Beckons

Night Beckons The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4)

The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4) The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1)

The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1) Lavender Vows tmhg-1

Lavender Vows tmhg-1 Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1)

Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1) Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

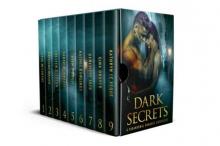

Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology

Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology Roaring Shadows

Roaring Shadows The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3)

The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3) The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1

The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1 The Chess Queen Enigma

The Chess Queen Enigma Sinister Secrets

Sinister Secrets A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8)

Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8) The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2)

The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2) Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10)

Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10) Sinister Summer

Sinister Summer Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4)

Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4) The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel

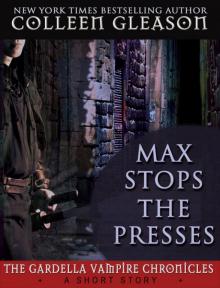

The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel Max Stops the Presses

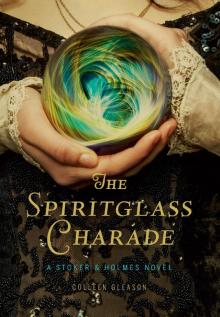

Max Stops the Presses The Spiritglass Charade

The Spiritglass Charade Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story

Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story Tempted by the Night

Tempted by the Night