- Home

- Colleen Gleason

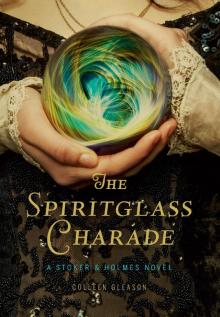

The Spiritglass Charade Page 9

The Spiritglass Charade Read online

Page 9

“I was told this was a murder scene,” he said after a moment of quiet perusal and air-sniffing. “Would you care to elaborate on that as well as on your presence here, Miss Holmes? Perhaps you know something about the victim that I do not.”

“She was a medium, a spirit-speaker. I attended a séance at which she presided yesterday”—he gave me an astonished look at which I set my jaw—“and presented some information that was very obscure. I came here today to determine how she’d come by this sensitive information, and to prove that she was a fraud. With a bit of observation, I’m certain you’ll agree with my deduction. Her landlady and I found her just like this. She was very frail yet seemed in good health, quite well-spoken, left-handed, and exceptionally adept at faking communication with the so-called spirit world.”

He trained his attention on the body, then the table, and finally at me. “Definitely murder.”

Miss Holmes

In Which Miss Ashton Makes a Startling Confession

Inspector Grayling was still investigating the murder scene when I took my leave nearly an hour later. Even more of a cognoggin than I, he employed a complicated device to take measurements of a faint set of muddy footprints on the windowsill, for we had both agreed that was how the murderer entered and exited the chamber. I watched him manipulate the slick footed mechanism, not even attempting to hide my fascination while it crawled about, clicking as it ticked off the numbers he needed.

It was when Grayling went on to employ a simple Eastman camera to make pictures of the area that I decided to take my leave.

Of course I had done my own examination, as well as completed a very satisfactory interrogation of the landlady and several of the neighbors. In addition, I’d collected a sample of the dirt at the window and was taking it home for analysis.

As I walked out of 79-K and looked for Dylan, I heard a horrible barking wail. Remembering the entertaining beagle pup that had been playing one level below, I hurried over to the side of the street-railing and looked down. To my dismay, it was indeed the creature. His hind leg had been caught in one of the metal grateworks that acted as a vendor-balloon mooring. He wailed pitifully, tugging and twisting and dancing about. I seemed to be the only person to hear the distressed sound over the normal city noises.

Before I could determine the best way to help the poor fellow, a figure came from nowhere, vaulting over the walkway’s edge and to the level below.

It took me only a moment to realize it was Grayling. He must have been working at Mrs. Yingling’s window and heard the distressed pup—then vaulted out and down to rescue the poor thing. He landed flat-footed on the lower streetwalk and had the little pup liberated in a trice.

I turned away, ignoring the odd feeling in my chest. What a foolish, dangerous thing to do, leaping out of a window and over the railing! I shook my head. Grayling could have easily misjudged his landing and gone tumbling down to the street level.

Tsking to myself, yet unable to dismiss the memory of the lanky detective vaulting smoothly from one street-level down to another, I walked off. Surely Dylan was in the vicinity, patronizing another meat-pie vendor or indulging in a flaming carrot. I needed to find him, for I had many things to contemplate in regards to my investigation. And I certainly didn’t want to be caught gawking at the Scotland Yard Inspector, either.

When I located my companion several blocks away, standing near the airship mooring dock, I launched into a description of my discovery of Mrs. Yingling’s body.

“She’s dead?” Dylan was, as I’d expected, eating again—this time a raisin-salad sandwich. The sweet rose-colored juice had stained the waferlike bread and wrappings, and a pink raisin plopped onto the ground as he took another bite.

“Not merely dead. Murdered.” I took his arm, noticing again how solid and firm it was. I was certain he could launch himself out of a window and down a street level too.

“What are you going to do now? Do you think it’s related to the Willa Ashton case?” He wiped the last bit of juice from his fingers as we strode along with me setting the pace at a brisk, efficient one.

“I hardly think Mrs. Yingling’s death is a coincidence. I suspect there is more to this case than a fraudulent medium trying to make money.”

Before I could expound further on my suspicions, we heard a loud mechanical squeal, then a violent crashing sound. Shouts and screams erupted from below.

People ran over to the edge of the streetwalks and looked down. A horseless carriage had crashed into another vehicle and overturned. A mangled bicycle was protruding from beneath the wreckage. Even from three heights up, I could see bodies on the street and splashes of bright red blood spilling over the cobblestones.

Bystanders were already helping to extricate the victims. A burly man and his companion heaved the carriage upright, and it landed on its two wheels with a loud thud. Others were arranging the injured persons on coats and blankets that had been laid on the filthy street.

Dylan’s arm was tight beneath my fingers, and I felt him move a little, as if to pull away. “I should go down there. See if I can help.”

“I’ll come with you.”

We hurried to the nearest street-lift and had to wait for it to return to our level. By the time we climbed on and it lumbered its way down to the ground, the police had arrived as well as some medical help.

I didn’t see the auburn-haired Grayling and assumed he’d been too far away to hear the accident, or perhaps on his way back to the Met by the time the incident occurred.

“Alvermina, what on earth are you doing down at this level?”

I whirled to find my famous uncle standing at the edge of the crowd. A tall, gangly man cursed with the sharp, Holmesian nose and receding dark hair, he brandished a walking stick.

“Hello, Uncle Sherlock.” I didn’t bother to answer his question and instead responded with one of my own. “Are you investigating a case? The missing boy from Bloomsbury, perhaps? I see Dr. Watson is here with you.” The shorter, bespectacled man crouched next to one of the accident victims.

“In fact I am on a case, but not the boy from Bloomsbury nor even the other from Drury-lane. The Met believe they have them well in hand, the fools, and have instead asked me to consult on a bloody fire on Bond-street. Might as well be sending me off to investigate the pickpocket gang. Waste of my brain cells.”

As Uncle Sherlock pontificated on Scotland Yard’s lapses in judgment and blundering attempts to investigate crimes, I noticed Dylan had approached Dr. Watson. They were speaking intently, gesturing to various accident victims in turn. My friend seemed very serious—even earnest. He stood slightly taller than my uncle’s companion, and despite his too-long hair, he appeared every inch a Brit. A handsome, confident young man who had garnered the full attention of the esteemed Dr. Watson.

Dylan looked as if he belonged. And as I watched him, I became aware of an unfamiliar sensation spreading warmly through my limbs.

I didn’t want him to leave.

“Do you not agree, Alvermina?”

My attention whipped back to my uncle. “Of course. And would you please refrain from calling me Alvermina?”

Uncle Sherlock blinked. “Whyever should I? It’s a magnificent appellation. A traditional family name, bestowed upon my grandfather’s mother. You are fortunate to have such an esteemed moniker.”

For being so brilliant in some things, my uncle could be quite cloud-headed in others. I was saved from replying by the approach of Dr. Watson and Dylan, the latter now wearing a defeated expression. Nevertheless, he greeted my uncle politely, and we watched the victims being loaded into medical cabs. When they were finished, there was nothing left to do but find our own transportation and continue on our way. My uncle and his companion chose to take a street-lift and therefore had to walk several blocks, but I was able to find a taxi.

“They can’t even give them blood,” Dylan muttered as we climbed into a horseless hackney. “Watson claims there are some instances when a blood

transfusion has been successful, but it’s very rare. And forget about surgery. . . .”

“Blood transfusion? Transferring blood from one person to another?” I had the exceedingly improper urge to sit next to him and pat his (ungloved) hand. He had changed from calm and controlled to bereft and confused, and he obviously needed comfort.

“It’s such a common practice in my time. It’s so frustrating to see things that could be so easily treated . . . and knowing there’s nothing that can be done with current medical practice.” He worried Prince Albert’s cufflink, still studding his tie. His expression was bereft. “It’s just not fair. It’s not right. I can see what needs to be done, but I can’t do anything about it.”

“I’m sorry, Dylan.”

He shook his head, his mouth a thin, dark line in the drassy light. “I need to go home.”

I nodded. He was right.

Despite my own desires, he didn’t belong here.

The next morning when I came out of my chamber, I found our housekeeper, Mrs. Raskill, vigorously dusting the fireplace mantel with her Spizzy Spiral-Duster.

I glanced toward my father’s bedchamber. The door was open a crack, a sure sign he wasn’t here. “Has he been home?”

Mrs. Raskill shook her head, then went about her dusting, but not before I saw a flash of pity in her face. “Not as of late.”

While everyone in London—perhaps England and even on the Continent—knew and lauded my uncle’s deductive abilities, only those close to the Prime Minister and the Queen knew how valuable my father, Mycroft Holmes, was to our national security. He spent his days at the Home Office, doing whatever it was he did to protect and serve the British Empire. And more often than not, he carried out the rest of the evening and night at his gentleman’s club in Mayfair.

In contrast, my uncle went out about on the streets and to the docks, dens, and rookeries as needed. He worked any case that appealed to him, whether it was for an individual of means, title, or not.

My father did all his investigating and strategizing from a desk and restricted himself to working for the government.

And yet . . . they both possessed the extraordinary Holmesian mind. My uncle acknowledged that, should Mycroft ever bestir himself and become physically active in his pursuits, he would outshine even Sherlock Holmes.

And I was his daughter—the child of a quietly brilliant, neglectful man . . . and a beautiful, vivacious woman.

Grief squeezed in my chest. I couldn’t help but look at the mantel, at the picture of my stunning mother. It was the only photo of her remaining in the house. And she, at least, had been aptly named: Desirée. The only visible trait I’d inherited from her was my thick, chestnut hair. Why couldn’t it have been her charming nose? Or her petite figure?

Mother left a year ago. I didn’t know why. It probably had something to do with my father’s style of life. But it could just as easily have had something to do with her awkward, bookish, socially inept daughter.

And it was one puzzle I no longer chose to contemplate.

She’d been in Paris at least for a time, for I received three short letters from her, each carefully devoid of anything pertinent. Even close examination netted me little information except that my mother had indeed written them, they had come from Paris, and she had to change ink bottles while penning one of them. The inconsistencies in her penmanship indicated many stops and starts during the composition, as if she’d had a difficult time determining what to write.

They gave no explanation for her sudden departure, other than vague platitudes like It’s for the best, and You’ll understand the reason someday, Mina.

The last letter came ten months ago.

“Mina?”

Mrs. Raskill had been speaking to me and I forced myself back to the present. “Yes, a pot of tea and some toast would be excellent.”

“And a piece of ham,” she insisted, pulling on the cord of her Spizzy for emphasis. The duster whirred softly as she lengthened the string, then when it was released, whizzed into an energetic spiral that she claimed did a much better job gathering up dust than a manual feather duster.

While Mrs. Raskill was preparing my breakfast, I sent a message to Miss Stoker wherein I invited her to join me in calling on Miss Ashton. It wasn’t because I was particularly fond of Evaline’s company or felt that she would be terribly helpful in my questioning of Miss Ashton, but more of a professional courtesy. After all, the princess had engaged both of us on the case.

I didn’t expect my so-called partner to accept the invitation, for I assumed she’d been wandering the streets of London all night, searching for the elusive UnDead, and would still be asleep.

To my surprise, the messenger returned with an affirmative response, indicating Miss Stoker and her carriage would call for me at half-past ten. The convenience of having private transportation made up for having to wait for her arrival.

I had finished my tea and toast and nibbled on a slice of ham under the watchful eye of Mrs. Raskill when the Stoker carriage arrived. Bundling up a generous reticule, I bid our housekeeper good day and left the house.

“Good morning, Evaline.” I commenced to settling in my seat. This was no simple process, for aside from my heavy skirt, ungainly bustles, and ever-present umbrella, I now had the cumbersome reticule to deal with.

“What in the blooming fish is in your bag? Are you going on a journey? Am I dropping you at the train station?”

“Tools and other accoutrements. After the surprise I encountered yesterday, I vowed I would never leave my house without my investigative equipment.”

“You look like a new governess, arriving at the door of her latest employer.” Evaline gave a merry chuckle. “Or a Gypsy woman traveling about.”

“At least I won’t be caught unprepared.” My reply was haughty, but I became acutely aware of how frumpy I must appear, lugging my large bag. I was dressed neatly, but practically, in a simple cocoa-brown and cream-striped bodice with a dark green skirt. My fingerless gloves and small top hat were dark brown and with only minor embellishments. In a sly nod to my cognog tendencies, I’d pinned my favorite mechanical firefly brooch to the left side of my bodice.

On the other hand, Miss Stoker looked quite fetching in her fashionable but unexciting handmaker clothing. Her frock was of fine quality and excellent tailoring (from Madame Burnby’s shop), and in a style that resisted the urge to be too lacy, flowery, or ruffly—and certainly not like the new Street-Fashion mode, which I found quite fascinating.

Although there were faint shadows under her eyes, Evaline’s gaze wasn’t dim or weary. Her daydress bodice was a lovely rose color, with a mauve underskirt and ruffles. The bonnet atop her head was little more than a fabric saucer, perched at her crown and slightly to the left. It had an elegant curve that allowed for the high bundle of her dark hair in the back, and was trimmed with tiny rosebuds and white daisies. I had coveted a similar one in a certain shop off Pall Mall, but it had more of a cognoggin element with a mechanized butterfly pin with wings that beat elegantly and some tasteful, gear-ridden flowers.

“Right, then. What surprise did you encounter yesterday, Mina?” There was a bit more levity in her voice than I appreciated.

“Mrs. Yingling’s dead body.”

Miss Stoker’s reaction to my blunt announcement was quite satisfactory. She goggled as she made a shocked noise.

Thus mollified, I proceeded to tell her of the events in detail.

“And Grayling agreed with you that it was murder? How in the blooming fish did you know?”

“Inspector Grayling only agreed with me after I practically spelled out the clues for him,” I informed her crisply.

“I see. Surely he was grateful for your assistance.” Her eyes danced. “So how did you know she’d been murdered?”

“Elementary, my dear Miss Stoker. Mrs. Yingling was left-handed, which I observed during our séance. But on the table where she had presumably been sitting and writing, as well as drinking,

her cup and writing instrument were on the right side of the papers. Clearly, someone else had been in the chamber and positioned the pen and cup to make it look as if she’d been working and then gone to bed afterward.”

My companion looked at me skeptically. “Maybe she moved them herself—accidentally bumped them out of place.”

“The angle of the pen and cup were both too precise and at the same time utterly wrong for having been randomly moved.”

“Maybe someone else was sitting there and writing.”

I shook my head. “The paper had smudges on it—the same sorts of smudges that a left-handed person makes because their palm brushes across the fresh ink as they write across the page. Someone else was obviously present besides Mrs. Yingling.”

“And so you think she was murdered simply because someone else was in the room?”

“Considering the fact that no one was seen coming or going from Mrs. Yingling’s chamber, the faint sweet smell I noticed immediately upon entering the closed room, and the raw redness around her mouth, it was quite obvious to me—as well as to Inspector Grayling, once I prompted him—that she had met with foul play.”

“So how was she murdered?”

“Poisoned. Asphyxiated with chloroform—which has a sweet, chemical smell. As I’m sure even you noted, the woman was very frail and elderly. It would take little effort to hold a rag over her face whilst she slept, and chloroform is a rapid, if not unpredictable, killer—and it can burn the skin. Hence the faint red marks I noticed around Mrs. Yingling’s mouth.”

“And then the murderer moved her pens and papers around?”

“Likely he or she was curious about whatever work the old woman had been doing, and was perhaps checking to make certain there were no incriminating notes therein. That was the perpetrator’s only mistake—well, besides not cleaning off his or her shoes—setting the scene on the table. If he or she had not taken the time to do that, I might not have identified the crime so readily. Either the culprit didn’t know Mrs. Yingling was left-handed, or didn’t realize the mistake when everything was arranged.”

The Vampire Voss

The Vampire Voss Lavender Vows

Lavender Vows Sanctuary of Roses

Sanctuary of Roses A Lily on the Heath

A Lily on the Heath A Whisper Of Rosemary

A Whisper Of Rosemary The Rest Falls Away

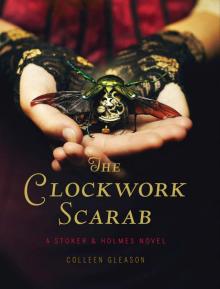

The Rest Falls Away The Clockwork Scarab

The Clockwork Scarab Roaring Midnight

Roaring Midnight The Vampire Dimitri

The Vampire Dimitri Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology

Countdown To A Kiss A New Years Eve Anthology The Vampire Narcise

The Vampire Narcise When Twilight Burns

When Twilight Burns The Bleeding Dusk

The Bleeding Dusk As Shadows Fade

As Shadows Fade Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5)

Sinister Stage: A Ghost Story Romance and Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 5) Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow)

Sinister Lang Syne: A Short Holiday Novel (Wicks Hollow) Sinister Sanctuary

Sinister Sanctuary Night Beckons

Night Beckons The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4)

The Carnelian Crow: A Stoker & Holmes Book (Stoker and Holmes 4) The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1)

The Shop of Shades and Secrets (Modern Gothic Romance 1) Lavender Vows tmhg-1

Lavender Vows tmhg-1 Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1)

Roaring Midnight (The Gardella Vampire Chronicles | Macey #1) Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

Lavender Vows (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology

Dark Secrets: A Paranormal Romance Anthology Roaring Shadows

Roaring Shadows The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3)

The Gems of Vice and Greed (Contemporary Gothic Romance Book 3) The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1

The Clockwork Scarab s&h-1 The Chess Queen Enigma

The Chess Queen Enigma Sinister Secrets

Sinister Secrets A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series)

A Whisper of Rosemary (The Medieval Herb Garden Series) Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Dark and Damaged: Eight Tortured Heroes of Paranormal Romance: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8)

Roaring Shadows: Macey Book 2 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 8) The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2)

The Cards of Life and Death (Modern Gothic Romance 2) Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10)

Roaring Dawn: Macey Book 3 (The Gardella Vampire Hunters 10) Sinister Summer

Sinister Summer Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4)

Sinister Sanctuary: A Ghost Story Romance & Mystery (Wicks Hollow Book 4) The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel

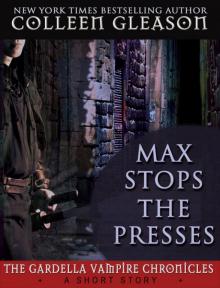

The Clockwork Scarab: A Stoker & Holmes Novel Max Stops the Presses

Max Stops the Presses The Spiritglass Charade

The Spiritglass Charade Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story

Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story Tempted by the Night

Tempted by the Night